Apple Breeding

Apples apples apples! We are in the thick of apple harvest, about halfway through our 10-week harvest time frame. And you are getting SO smart about apples, I can tell! In my last post, I talked about those specialty apples and why they’re just so special. I mentioned that they are developed through apple breeding programs and that I’d talk about that in the future. The future is here! So let’s talk about apple breeding and how these universities go about developing the next best apple variety!

First and foremost, it’s important to know that apple breeding is not done in a lab. Personally, I am not against genetic modification when used for altruistic purposes. I think it is an amazing feat of science that can do a lot of good for our suffering earth – reducing pesticide use, increasing the nutritional value of food, and even saving lives. But THAT is a completely different subject matter and one that can be deeply controversial. For today, I want to talk about the apple breeding, or more perhaps accurately, apple selection, that is being done out in the field at select universities and organizations across the world.

In apple breeding, experts are simply mimicking the natural processes of the apple life cycle, but in a more controlled environment. I’ve explained in past posts that apple blossoms require pollination by a completely different apple variety in order to set fruit. And if you remember, it is the seeds of the developing apple that are the offspring of the blossom variety and the pollen variety. And if you were to plant those seeds, you’d get completely new and wildly unpredictable apple varieties. But what if you were able to take away some of the variables that could potentially produce unpalatable apples? What if you started with the blossoms of a delicious apple variety and you KNEW they were pollinated with the pollen of another delicious apple variety? Wouldn’t you be more likely to have at least a chance for a delicious new apple variety? Essentially this is what scientists in apple breeding programs across the world are doing.

These scientists begin the process of developing a new variety by doing a controlled cross of two known apple varieties. These varieties might both be delicious, and they want a new REALLY delicious offspring. Or maybe one of the apple varieties is delicious, and the other variety has shown some disease resistance. So the offspring could potentially be a new disease-resistant delicious variety. The experts in these breeding programs carefully consider several different traits that make an apple marketable – appearance, taste, texture, growth, etc. When they think they have a winning combination, they use a controlled cross-pollination technique.

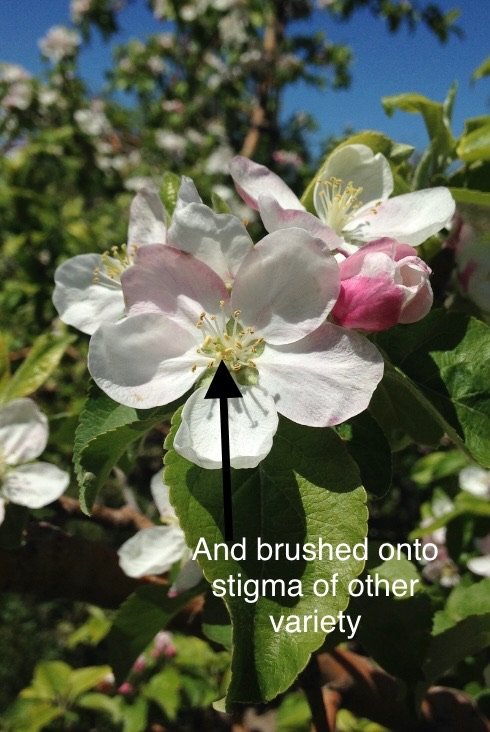

Let’s use an example of some varieties of apples you might be familiar with. SweeTango is one of those delicious, amazing Specialty apples developed through the breeding program at the University of Minnesota. It is a cross of Honeycrisp (another delicious, amazing Specialty apple) and Zestar (an early season, lesser-known variety). After deciding these two apple varieties might make a tasty baby, scientists went to a known Zestar apple tree during peak bloom and collected Zestar pollen with a tool (often just a simple paintbrush). They then went to a known Honeycrisp tree that was also in bloom and brushed the Zestar pollen onto the just-opened female parts of the Honeycrisp blossom. Now they know that every single ovule that gets fertilized on that one blossom will be a Honeycrisp/Zestar mixed apple seed. Now they isolate that one flower with a mesh bag that allows air and sunlight penetration but does not allow any errant pollen to enter. Once the apple blossom fades and the baby apple starts to grow, the bag is removed but the branch is marked so scientists can track that particular apple’s growth. Once that one single apple is mature, the scientists collect the mature seeds inside the fruit (if they were smart, they’d snack on the discarded apple – it IS a Honeycrisp after all!), germinate them in the nursery, and now they have 5-10 brand new Honeycrisp/Zestar apple trees.

But brand-new trees take a while to mature, blossom, and fruit. So, it’s another 3-5 years before anyone is even able to sample what these new Honeycrisp/Zestar apples taste like. And maybe only a couple of those apples are any good at all. Well, now the scientists take cuttings from those pretty good Honeycrisp/Zestar trees and they graft a bunch of duplicates (remember your grafting lesson!) to plant out in an orchard setting to make sure these new varieties can withstand cold winters, insects, and disease attack, yearly harvests, etc. Once they find one apple variety that passes all those tests – taste, texture, field trials, storage – THEN it’s time to grow more. At that point, the breeding program would partner with one of those grower cooperatives to focus on naming and marketing this brand-new variety. And thus, the SweeTango was born!

This process takes years and years to complete, though. The original cross for SweeTango was done in 1988 and the variety was officially released in 2007. That’s almost 20 years of research, trials, and effort by the breeding programs and the cooperatives.

Today, there are several main breeding programs in the US – at the University of Minnesota, Washington State University, Rutgers/Purdue/Indiana, and New York’s own Cornell University. Cornell is the oldest breeding program in the United States – they have been studying apples and developing new varieties for over 100 years! The newest apples to come out of Cornell’s breeding program are SnapDragon and RubyFrost, both now available in our Upick sales pavilion. But there are breeding programs all over the world, each one using these same techniques to develop unique and fantastic new apple varieties.

So the next time you crunch into a Snapdragon, or juice drips down your chin from a Honeycrisp, take a minute to acknowledge all the time and effort that went into developing these amazing apple varieties, and know that it all started at the core of one single apple.

All the best,

Katie